COMPILED AND EDITED BY CLYDE BEAL

APRIL 2005

PURPOSE: The following account was prepared to compile all of the knowledge and legends of this venerable and historic gristmill in a single document. Every effort has been expended to make it as factual as an amateur scribbler can make it. To the best of the author’s ability, the facts presented are true and those that cannot be verified are so noted.

Any errors or omissions are the fault of the author and none other.

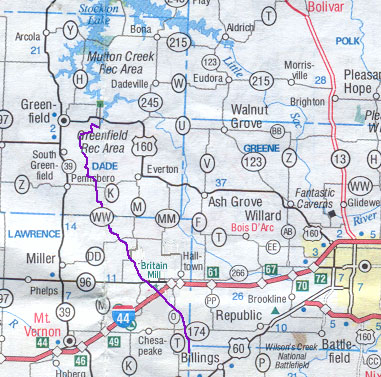

INTRODUCTION: Turnback Creek is the beginning of this story. Without the presence of this happy, babbling stream there would be no gristmill and therefore no story. The creek begins in springs located near Billings, Missouri, about 30 miles south of the gristmill as the crow flies. It makes a detour westerly for ¼ mile just before it reaches the dam that serves to provide a reservoir for the mill. The creek turns north again on its way to its terminus in Lake Stockton, another 60 miles, or so. See the map below with Turnback Creek shown in purple.

Turnback Creek is second only to the Sac River in terms of volume delivered to Lake Stockton. Its diminutive designation as a creek must have been made recognizing the higher importance of the slight larger stream. Nevertheless, Turnback Creek is head and shoulders more important than all other water ways, as far as Britain Mill is concerned.

The recounting of the available history of this place will list all of the dry facts that still exist and offer some speculation on those that no longer can be verified. The reader should not expect to be entertained, unless the history of old gristmills is of special interest. The author’s meager collection of skills does not include those of a witty or clever writer.

A large portion of this account is taken from the writings and oral discussions by Bill Cameron, who restored the current structure. He did not leave bibliographies of his sources of information, nor were all of his words always consistent in subsequent publications. However, there is little doubt that Cameron was trying to be accurate and true to his love of mills.

The mill discussed herein was known by several names during its lifetime. Those of which have been seen in documentation include, Turnback Mills, McCoy Mill, Likins Mill, and Britain Mill. The latter is favored for the current designation for two reasons; 1) it was the last name under which commercial operations were conducted, and 2) the Britain family owned and operated it longer than any of the other owners.

EARLIEST GRISTMILL: James and Matthew Sims built the first mill. Property records show that they bought ten acres from Washington Smith , the first sheriff for Lawrence County, in 1852. Two years later, a land patent was issued to Mathew [sic] Sims for the 40 acres adjacent to the first ten acres.

The true identity of James and Matthew Sims is unclear. The 1850 census, the earliest of Missouri, shows a Sims family in the Ozark Township (now designated as Township 29) the location of the mill property. This family was headed by a Matthew Sims, age 38, and Nancy, age 39. There is an 18-year-old, James, who was presumably the son of Matthew and Nancy.

To confuse matters, nearby were James Sims , age 68 and Julian, age 61. One can reasonably assume that Matthew was the son of the elder James. Both could have been the purchasers of the property.

However, there was also a Matthew Sims in nearby Mt. Vernon Township, who at age 60 could well have been the brother of James, age 68. Further complication is the presence of James Simms (2 m’s), age 29, in the same Township with six children, one of who was named Matthew!

Assuming that Matthew, age 38, was still living at the time of the eventual sale of this property, it is my conclusion that he and James, age 68, were the owners and operators of the first mill. This logic follows since Nancy Sims’ name (Matthew’s wife) also appears on the deed when the property was sold.

The construction of the first mill is reported between 1839 and 1845. It seems possible that any of those dates are valid, since Lawrence County wasn’t founded until 1845, when property records began to accumulate. One possibility is that the Sims squatted the land, but didn’t bother to buy it for some years later. This procedure was common at the time. Moreover, the Sims’ first site was not on the ten acres purchased from Smith, but was some distance upstream . Notes from the previous owner, Vivian Boswell, suggest it was approximately 50 yards upstream, but the source of the information is unknown.

According to the restorer, Bill Cameron, Sims partnered with Oliver P. Johnson in 1854 , who installed a carding machine in the mill. O. P. Johnson also had a carding mill and a sawmill on nearby Johnson Creek and served as the postmaster for Paris Springs in 1882. However, property records show that the partnering occurred later with another Johnson and the Likins family. (See below.)

EXPANSION: The Likins family is thought to have been of Quaker stock, relocating to Missouri in stages from Tennessee between 1843 and 1851. In the records found during this research the spellings of the family name is about equally divided with “Likins” and “Likens”. The former has been chosen for this author by virtue of its consistent use in the records of deeds of Lawrence County. It is presumed the succession of clerks had a signed copy of the deeds in front of them.

The family had followed a pattern of interdependent immigration and settlement in the move to Missouri. Like other yeomen farmers from the Upper South the Likins employed this strategy in their settlement of the Salt River Valley in northeastern Missouri. Family members would move in concert or serially, establish farms in close proximity to each other, and then intermarry. In effect, they transplanted the extended family network to the settlement area and then maintained the network through marriage of closely related individuals. The strategy allowed family members to pool labor and other resources while establishing themselves and provided a defensive network, if needed.

The families were farmers/tradesmen, settling first in Greene County, MO. William started in the milling trade when he bought his first mill in 1853 with a family partnership. William and his son George S. then acquired Turnback Mill as part of their expanding milling business in 1857. This mill was replaced or rebuilt by the Likins shortly after its acquisition. The restored mill now on the site is an attempt to recreate the mill that stood here after the Likins rebuilt.

The house up the slope from the mill was built for Charles S. Likins and his bride, Sarah Ann Adams, in the mid-1800’s, replacing an earlier log cabin. The house was originally a three-room structure with large sandstone fireplaces on each end and a porch across the entire front. Subsequently, a wing was added to the rear and a summer kitchen on the west side.

In 1859, the Likins deeded ½ ownership in their property including the mill to George Johnson. There is no record of the nature of the partnership. Indeed, no George Johnson appears in the US Census for Lawrence County between 1850 and 1880. It is possible that this Johnson was a silent partner, providing capital. Moreover, a G. H. Johnson is noted as a neighbor and mill hand in the Likins mill operation Greene County.

During the Civil War the Likins were Unionists, as was the majority in Lawrence County. Three members of the family, including Charles S. enlisted in the Federal Army. Sarah Ann’s brother, John Adams, may have operated the mill during that period. Neither of their mills was destroyed during the war, although local legend claims at least one skirmish occurred near Turnback Mill.

In fact, the First Kansas Volunteers camped at what is now Paris Springs, half a mile downstream from the mill, for a few days in July, 1861. One soldier’s letter survives, recounting an encounter with a Rebel cavalry patrol and the Union pickets. The same soldier mentions that the mill “…is at work night and day…” providing the troops with much needed flour.

Around 1892, the Likins family expanded Turnback mill to a two-storied structure and about doubled the footprint of the prior building. The 36” Bradford buhr was replaced with a Great Western roller and a Leffels water turbine was installed.

Multiple accounts mention that the Likins modifications replaced a paddle wheel. The implication being that a water wheel may not have been in use originally at this site. A paddle wheel makes sense for this stream, with little fall, even from a dam 200 yards upstream, but a good flow rate. Another possibility is that the paddle wheel was replaced with an undershot or breast wheel during the first Likins’ remodeling and replaced again when the turbine was installed. The latter is most probably, given that the remnants of a wheel box remain at the south end of an earlier mill configuration.

The wheel box appears to be suitable for water wheel, or paddle wheel about four to five feet in diameter and six feet wide.

It is sited in a direct line with the original millrace before the turbine pit was constructed and the race diverted. The topmost layers of rock are distinctly different from the lower courses. This suggests that the original flume for the wheel well was about half as high as the concrete corners in the photo. The wheel well likely is c. 1857.

Thirty-nine years after the Likins bought the original 50 acres; the property had grown to at least 95 acres. It was sold to G. John McCoy in 1896, who gave it to his son, Norman. Norman apparently operated the mill from the beginning.

McCoy produced at least four brand names in the mill; Harvest Girl corn meal, Oven Buster high patent flour, Lily Rose half patent wheat flour, and Choice Family flour. The brand names were continuation of brands used by the Likins.

A tale from the McCoy era was his practice of helping school children that had to cross the log footbridge across Turnback Creek on their way to school at Paris Springs. It is said that McCoy would shut down the water wheel during bad weather and personally assist in the crossing, endearing himself to the neighborhood mothers. Perhaps Norman was the prototype school crossing guard.

McCoy is given credit for adding the office lean-to to the building and for using a steam tractor for temporary power during the drought of 1902. Norman, however, did not keep the building and equipment in good repair.

After about fifteen years in the milling business, Norman McCoy sold the mill and 64 acres to John F. Hockery, a millwright living in Republic, MO, in 1911. Hockery apparently repaired and improved the facilities and then sold to John W. Britain in 1912, about seven months later.

This photo reputedly shows John Britain standing on the right. The structure is at its maximum size with a covered loading dock and the lean-to office.

The support structure at the far left is for the turbine-operated drive shaft.

MATURATION: At about the time of the Britain acquisition, the independent, small gristmills were beginning to be threatened by larger scale operations made possible by much cheaper transportation. The Britain family continued to operate the mill and to support subsequent generations, but expansion of the mill had ceased by then.

John Britain hired his nephew, Alva Britain, a millwright and miller, to operate the mill. About three years later, Alva moved his family to Monett, MO, to manage a larger mill. To replace Alva, John Britain’s daughter, Bette, who was the bookkeeper and office manager, learned to operate the buhrs and flourmill.

Eventually, John’s son, “Wash” Britain assumed responsibility for the milling operations, moving his family back from Seattle, WA. He was creative and a good merchandiser. He made, mixed, and marketed the first locally produced self-rising flour. He then switched to feed stocks for poultry and cattle. He installed a power unit for operation during times of low water.

In the mid-1940’s the dam was dynamited, perhaps by fishermen or perhaps by farmers concerned about flooding. Wash Britain by then was in poor health and had serious trouble in finding trained help for the mill. He reluctantly elected to discontinue commercial operations, resulting in the mill’s gradual physical demise.

After over a century of successful production and a center of community life, the mill was retired, yielding most of its machinery to scrap dealers.

RESTORATION: The restoration resulting in the current structure was the inspiration of Bill Cameron, an Irish immigrant with an especially colorful and varied history. As a youngster he ran away from Ireland to Scotland, where he was regarded as “dirty Irish”. He ended up serving in WW I in the Royal Irish Fusiliers, wounded three times in France. In 1923, at age 25, Bill arrived in the US and began a sales career in St. Louis. Most of his efforts were in the milling trade; belts, machinery, and supplies.

Bill had the distinction of being the oldest Missouri draftee for WW II. After the war he married and started his own feed mill in Exeter, MO. Over the years, the Camerons were involved with the School of the Ozarks in Lookout, MO.

His bride, Letha, was his connection to Britain Mill. She spent a few months at the mill with Alva Britain and his wife after her mother died when she was four years old. Bill later wrote that her memory of that time was one of the fondest of her life. Cameron convinced Wash Britain to lease him a portion of the land in order to construct the restored building as a memorial to Letha.

Without much money with which to work, he used his wit and salesmanship to enlist volunteers and contributions of materials to his enterprise. Personal accounts from his helpers confirm that Bill put in many, many hours himself in every phase of the construction, even at his advanced age. He was 80 years old before the construction was completed.

The restoration is a rough approximation of a typical mill structure in the mid-19th Century. A sketch of Cameron’s original concept shows a more complicated structure than that which finally evolved.

Initial Restoration Design

In the above sketch the concept of using both a water wheel and the turbine is shown. However, the turbine pit was not in place at the time of the original mill. Additionally, the office structure on the right was not present until 1900-1910. The sluice leading to the water wheel probably never existed before the restoration. Cameron likely made the compromises to keep the construction costs within available funding and to provide a finished product that would be commercially viable.

The above sketch depicts the mill site today. In this view it is apparent that the original mill was not located where the existing structure stands. The “original wheel well” is framed by stonewalls which probably formed part of the old mill’s foundation. The wall terminates at the concrete turbine pit, which was built later. Indeed the old wall is very nearly in line with the front foundation of the existing structure. One could be the continuation of the other, having been extended when the Likins family expanded the mill in 1892.

Bill Cameron had a vision of operating the mill for profit eventually. His intent was to sell “naturally grown meal”. He apparently was able to drive a horizontal mill and a side grinder using electric motors, but the waterpower was never restored.

A nephew of the Britains was permitted to attempt to restore the broken dam. By contemporary accounts the nephew was less than qualified and a lot of wet concrete washed down Turnback Creek. Whether for lack of waterpower, other conflicts with Wash Britain, or the lack of a niche market, Cameron abandoned the commercial effort shortly after completing the restoration.

After the restoration project, the property passed to heirs of Wesley Britain and eventually to Marvin and Bonnie Boyd, in 1981. Marvin was a cabinetmaker and used the old house as his shop. There is some evidence that he may have used the mill office also. Other than possibly installing a plywood ceiling and insulation and security screens on the windows in the mill office, the Boyds apparently did not make any repairs or modifications to the mill.

In 1988, the property sold to Vivian Boswell, an artist specializing in botanical painting. Besides a significant renovation of the living quarters across the road from the mill, she restored the dam. This project required about a year just for the formal approvals by the Missouri authorities and the Corps of Engineers. In early 1993, the water began flowing over the new spillway. Four months later a five-hundred-year flood washed away all of her efforts, making the dam useless again.

The restored dam in January 1993

This flood reportedly reached nearly to the eaves of the current mill structure and may have briefly risen above the SR 96 bridge just downstream. The flood silt was largely removed from the mill eventually and a new roof over the lean-to office was added. The roof was installed above the original roof, so that both are still in place today.

A few years later, Ms. Boswell permitted a production company to use the mill in a scene of the movie A Place to Grow. The company parked two 18-wheel tractor trailers near the mill and proceeded to film a love scene for this movie starring Wiford Brimley, with Chris Kristofferson (the daughter of Chris K.), and Boxcar Willie, among others. The film was released in the summer of 1998 and premiered in Springfield. Ms. Boswell received remuneration for the use of the property of a princely $1.00.

REHABILITATION: In 2002 the property transferred to Clyde & Janet Beal. In early 2004 a project was initiated to renovate the mill and equipment to an operable state.

Harold Sullins, of Lickin, MO

A project manager was engaged to provide technical consultation and construction skills for the rehabilitation. Harold Sullins, of Lickin, MO, agreed to help, using his knowledge of mill operation and maintenance acquired as an employee at the Montauk State Park, Salem, MO.

Equipment present at the start of the rehab included:

O 16” Meadows Mill Vertical grinder, driven by a 5 hp electric motor, acquired by Bill Cameron from the Silver Lake Mills in Phillipsburg, MO.

O Bernard & Leas, Model 1 bran duster, originally in this mill in 1892. It was sold to the Hodgson Mill for its restoration, but returned to Bill Cameron.

O A.T. Ferrell Clipper, model M-2B, seed cleaner

O safe marked with “Turnback Mills” above its door

O J. Leffels water turbine, dated January, 1862

None of this equipment had been cleaned since the inundation of 1993. It was richly endowed with silt, mice nests, and a few crisp carcasses.

The floor and ceiling of the office had collapsed and the west wall was separated from the main structure by about 10 inches. The roof shingles were badly deteriorated, having been installing about 30 years earlier. The water wheel was severely damaged from weather and falling debris. Most windows were broken and significant deposits of flood silt remained.

The project goal was to restore the operations sufficiently to demonstrate to selected visitors how a custom mill might operate in the mid-19th century in the Ozarks. Initially, the existing equipment was cleaned and restored. The bran duster was fitted with screens for corn meal and grits to serve as a sifter, eventually. The restoration of water power was deferred for a later time, so plans for electrically powered equipment were made.

A new beam at the rear of the mill was installed on which a line shaft was mounted. A motor in the overhead now powers the shaft. The new line shaft drives flat-belt pulleys for an elevator and sifter. Two elevators from a large feed mill were donated from which came the single unit that serves the Meadow Mills grinder and the modified B&L sifter with a newly constructed chute.

The structure has been repaired with new shingles, office flooring, and windows. Additional lighting was installed in the main structure. Artifacts have been labeled and mounted inside the mill and a modest picture collection of the mill’s history displayed.

Outside, the sluice was dredged of accumulated silt, fences mended, and trees pruned. The site of the original water wheel has been excavated.

The restored mill was once again ready for inspection for those interested in early Ozark settlements. It provides a hint of some of our history long past. Its conditions are certainly not as it would have been in the mid-19th Century. With eighteen-wheelers thundering on nearby SR 96, electric lights and motors, and the absence of the rumble of large grinding stones, it can scarcely be a true representation.

However, with a little imagination one can get the sense of some of the challenges of early mills and the ingenuity employed by their operators to overcome them. Sometimes if you listen carefully, you can imagine hearing the spinning of yarns on the old loading dock, as the millrace gurgles nearby.

In 2024, after 20 years of renovations and upkeep, the property changed hands again following the passing of Clyde Beal.

Bibliography

Lawrence County, MO, Deed Records, Book D, pg 585

[1] Ibid, Book E, pg 325

[1] 1850 US Census, District #47,entry #366

[1] 1850 US Census, District #47, entry #367

[1] 1850 US Census, District #47, entry #410

[1] Meyer, Duane G., The Heritage of Missouri, 3rd Edition, Emden Press, Springfield, MO, 1982, pg 238

[1] Cameron, Bill; The Ozarks Mountaineer, July-Aug 1980, pg 48

[1] Ibid

[1] A Reprint of Goodspeed’s 1888 History of Lawrence County, Litho Printers of Cassville, MO, 1973, pg 165

[1] Private correspondence, Kerry C. McGrath to Vivian Boswell, w/ accompanying Historic Site Nomination documentation, dated 7 Dec 1991

[1] Lawrence County, MO, Deed Records, Book D, pg 586

[1] McRaven, Charles, Old Mill News, July 1978, pg 3

[1] Private correspondence, Kerry C. McGrath to Vivian Boswell, w/ accompanying Historic Site Nomination documentation, dated 7 Dec 1991

[1] A Reprint of Goodspeed’s 1888 History of Lawrence County, Litho Printers of Cassville, MO, 1973, pg 71

[1] Hatcher, Richard W. and William G. Piston, Kansans at Wilson’ Creek: Soldiers Letters from the Campaign for Southwest Missouri, Wilson Creek National Battlefield Foundation, 1993, pg 61

[1] Gunter, Nolan, The Ozarks Mountaineer, March 1968, pg 9

[1] Boyd, Don, Ozarks Highways, Winter 1972, pg 10

[1] Lawrence County, MO, Deed Records, Book 73, pg 103

[1] Photo, annotated by Bill Cameron, in the author’s private collection

[1] Gunter, Nolan, The Ozarks Mountaineer, March 1968, pg 9

[1] Cameron, Bill, The Ozarks Mountaineer, July-August 1980, pg 49

[1] Lawrence County, MO, Deed Records, Book 121, pg 78

[1] Ibid, Book 122, pg 71

[1] Cameron, Bill, The Ozarks Mountaineer, July-August 1980, pg 50

[1] McRaven, Charles, The Ozarks Mountaineer, Feb 1974, pg 23

[1] Ibid

[1] Private correspondence, Charles McRaven to Clyde Beal, 10 Dec 2004

[1] Author private collection, undated hand-written note by Bill Cameron regarding the provenience of B&L Bran Duster